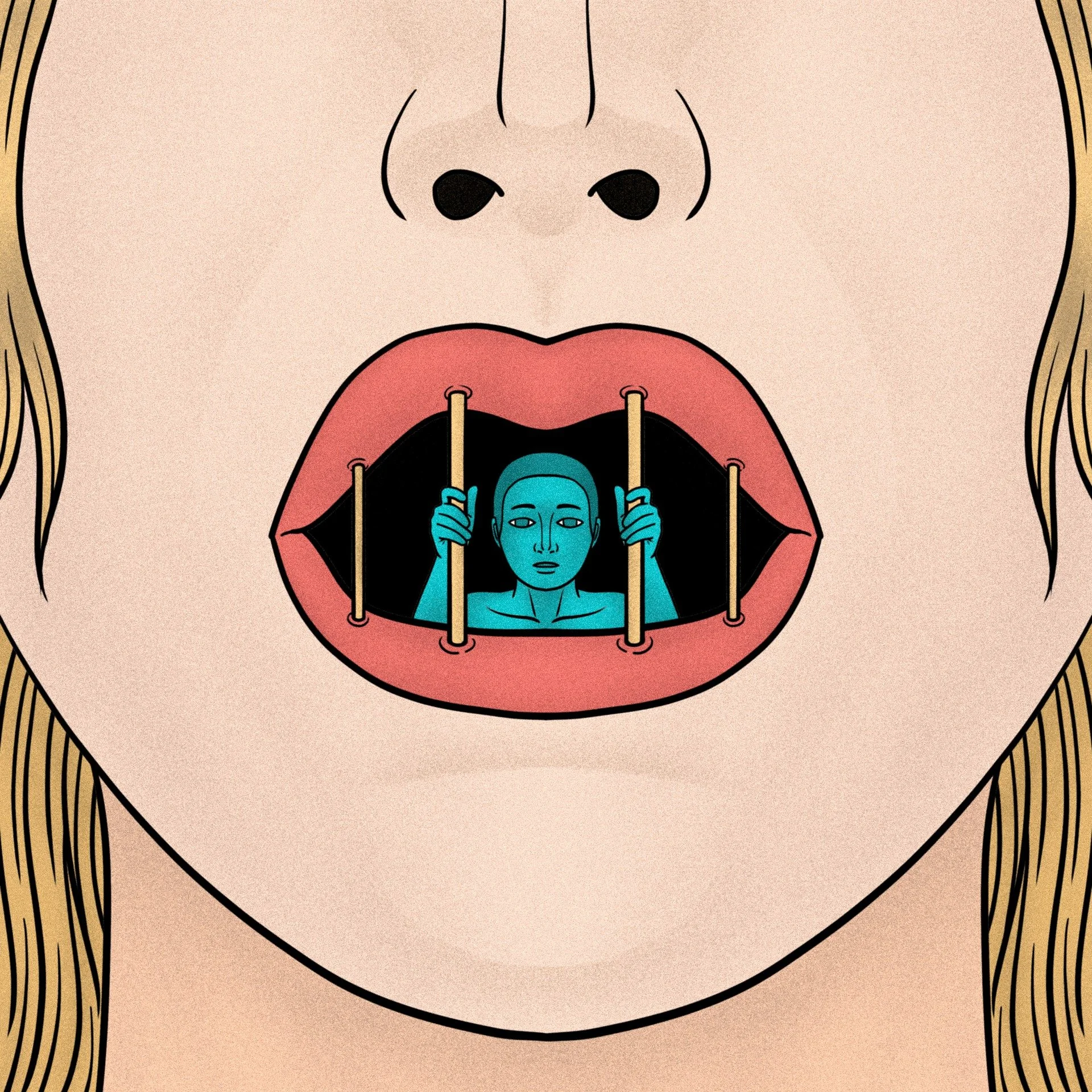

Silencing Dissident Voices: Why Freedom of Expression Matters

Central to the agenda of those who would subvert democracy is the attack on freedom of expression. The goal of this attack is to silence dissident voices. There are many ways to do this. It can be done by shutting down civil society: closing public forums, media outlets, and the arts. It can be done more definitively by imprisoning those giving expression to unapproved thoughts and ideas: “Lock her up.” And, most definitively, it can be done by killing those who dare to make their dissident thoughts known.

But where does the need to silence dissident voices originate? Why do some people care so much about what others say and why is freedom of expression important to those who would speak their minds?

Whatever form silencing takes as a political and cultural reality, its intent is always to get inside our heads, to create in all of us a special state of mind in which the attachment of anxiety to the act of self-expression is the central feature. This is the goal, and this is the site of struggle over freedom of expression. It is why freedom of expression matters to those who would restrict its scope or eliminate it altogether. But where does the need to silence dissident voices originate? Why do some people care so much about what others say and why is freedom of expression important to those who would speak their minds?

To explore these questions, I would like to begin with an experience I had my freshman year in college. This was not an experience with freedom of speech as such but an encounter with the question: Why does freedom of speech matter? The encounter occurred during an introduction to political science course. At the time, I had little idea what political science was, but I had already decided to major in one of the social sciences and, to decide which one, I enrolled in an introductory course for each of them. I now remember very little that happened in the classroom during my college career, but one event remains a surprisingly vivid memory. It was the day the professor in my introductory political science class walked into the classroom, looked out at his students, and asked: Why do we have freedom of speech? My immediate response to the question was: I don’t know. But some of my fellow students thought they did. To each of their proposed answers, however, the professor politely offered cogent reasons why they were less than compelling, which led me to draw the same conclusion. And that was where we left the conversation. The professor made no effort to sum up the discussion or provide us with the correct answer. The bell rang and out he walked.

I still remember walking across campus after class struck by the realization that I had no idea why we have, or should have, freedom of speech. Yet, while I did not find out why we have, or ought to have, freedom of speech, I did learn something important that has stuck with me ever since. What I learned was that, if you don’t know why something is true, don’t assume that it is, or, put another way: You should never allow the process of thinking to be limited by a conclusion known in advance. If you don’t know why freedom of speech is important, you don’t know that it is.

The experience I had in college and the lesson driven home by it seem especially relevant today when the norm of freedom of speech is being challenged [2,3]. As one commentator puts it:

I have never in my adult life seen anything like the censorship fever that is breaking out across America. In both law and culture, we are witnessing an astonishing display of contempt for the First Amendment, for basic principles of pluralism, and for simple tolerance of opposing points of view. [1]

For many people, freedom of speech doesn’t seem to matter, or it doesn’t matter very much. For some, it matters that they are free to say what they want even when (or especially when) what they want to say demeans others. But they have no interest in affording an equal right to say what you want to those who might demean them. For these people, freedom of speech seems more an entitlement to engage in acts of verbal aggression than an expectation that they will respect the rights of others.

It can also be said that most people have little or no opportunity in their lives to exercise freedom of speech in any meaningful sense of the term. They do not write columns for the newspaper, aspire to public office, or participate in public protests. They are not university professors for whom the right to freedom of speech is, or at least once was, the most cherished of rights. For most people, the right to speak their minds outside the privacy of their homes is used very little, or not at all. So, why should it matter to them? And, if there are enough of those for whom freedom of speech doesn’t matter, why should we expect much resistance when the right to freedom of speech finds itself in jeopardy?

For most people, the right to speak their minds outside the privacy of their homes is used very little, or not at all.

For me, thinking about the recent conflicts over freedom of speech brought to mind the experience I had in my political science class. While, at the end of the class period, I did not have an answer to the professor’s question, there was an answer embedded in the class discussion and in the moment of enlightenment it provoked. My insight into the importance of not taking the answer to questions for granted pointed me in the direction of mental processes that take us away from the comfortable world of the already known. As it turns out, thinking your way into the unknown is the essence of freedom of thought, and freedom of thought is, I think, the essence of freedom of speech.

By freedom of thought, I have in mind the free movement of thoughts, which is something we associate most notably with the process of free association. The more our thought process is open to the arrival of unexpected, even unwanted, thoughts, the freer it can be said to be. The alternative to the free movement of thoughts is the restriction of thought to familiar paths and familiar conclusions. Since this is a restriction on thoughts, it is a restriction enforced internally.

This development can be blocked when, early in life, self-expression is found to be a dangerous thing to do.

While it may be tempting to assume that thinking your way into the not-already-known world is a simple matter of deciding to do so, this is not the case. Assuming that we can simply decide to think our way into the unknown treats that process as an innate capacity. But we will do better if we treat it as a developmental achievement dependent on the internalization of a specific kind of experience. This development can be blocked when, early in life, self-expression is found to be a dangerous thing to do. It is dangerous because it provokes loss of connection to the source of the good things: the good object. When that is the case, the consequence of exercising the capacity for engaging the unknown is that we will be on our own in a dangerous world. If our formative relationships involve aggression and withdrawal as a response to self-expression, internalization of those relationships creates internal restrictions on where our thoughts are allowed to lead us.

For many people, much is put at risk in embracing freedom of speech, most notably the risk attendant on making their forbidden thoughts known to others. This risk develops when connection with others is based on sameness of thought. If sameness of thought is the only viable way of making a connection that we have, freedom of thought means loss of connection. This means that having an inner world conducive to freedom of thought requires that our connection with the good object is not put at risk when we differentiate ourselves from it and exist as a person in our own right.

External prohibitions on speech are judgments about our thoughts, which means they are judgments about what goes on in our inner worlds. Prohibitions on speaking are also attempts to prevent us from having prohibited thoughts and being the kind of person who has such thoughts. They are an attempt to deprive us of freedom of thought. For this to work, the external prohibitions have to get inside our heads. And, they have to do so in a way that disconnects the prohibited thoughts from us, makes them no longer our thoughts. Even if we cannot rid ourselves of our bad thoughts, we may be able to rid ourselves of responsibility for them by shifting that responsibility onto others so they will not be our thoughts but theirs. We do not have our thoughts when we experience them as the thoughts of other people.

The more powerful our need for approval, the more our primary task in making our way through life becomes learning what are the approved thoughts and acting as if the approved thoughts are ours even though they are not.

But to solve the problem created for us by our bad thoughts, it is not enough to move them into external containers. It is also necessary to replace them with thoughts that protect our connection to the source of the good things. These are thoughts whose expression provokes approval. The more powerful our need for approval, the more our primary task in making our way through life becomes learning what are the approved thoughts and acting as if the approved thoughts are ours even though they are not. Within this world of meaning, what assures the attachment of the individual to the ideal of freedom of speech is his or her sense that freedom of speech is among the good (approved) thoughts. But advocating freedom of speech because it is an approved thought makes freedom of speech problematic since it ties freedom to a force (the approval process) mobilized to constrain what can be thought and therefore also what can be said. It makes freedom of expression a fixed point, something we must not question.

Given this link of freedom of speech to violence, it is not surprising that, while we insist on our own freedom to speak, we do not recognize a comparable right in others.

If we are not free to have our thoughts, it is reasonable to say that the thoughts we can have are not our own; they are placed into our minds by someone else. They are determined by the approval process originating outside and internalized as a prohibition. If that is the case, we might not experience the freedom to express our thoughts as real freedom, but something closer to the opposite of it. And, if this is our experience of freedom of speech, we are hardly likely to make any significant positive emotional investment in it. If we have a use for freedom of speech, it is likely to be as a weapon mobilized against those thoughts of others that we need to suppress. This freedom, when expressed in acts of verbal violence, is what freedom of speech means for us. Given this link of freedom of speech to violence, it is not surprising that, while we insist on our own freedom to speak, we do not recognize a comparable right in others.

At its best, freedom of speech protects freedom of thought and freedom of thought reduces the pressure to move bad thoughts outside and make their external containers targets for our aggression. At its worst, freedom of speech creates a protected space for acts of verbal aggression and encourages the use of others as containers for our bad selves. When freedom of speech is connected not to the destruction of but to respect for differences, it is a freedom deserving of the name. But whether freedom is essentially a license to assault or the external expression of freedom of thought depends not primarily on the way social policy shapes and limits speech but on the way the formative experiences of the individual make inner freedom a reality. After all, what meaning can there be in a right to do something when relating to others you cannot do when relating to yourself?

Freedom of expression is a norm whose purpose is to prevent people from incorporating others into their internal dramas. The more widespread and powerful the need to incorporate others into those dramas, the weaker the support for norms of freedom of expression and the more likely the success of movements to undermine those norms. Those who are committed to freedom of expression as a norm would do well, therefore, to pay more attention to the factors in the development of the personality that make adults ill equipped to tolerate hearing the expression of thoughts and ideas that establish their lack of control over what others think and say.